SPRING 2003

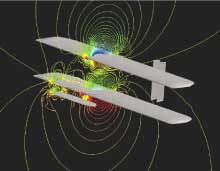

A computer simulation shows the plot of pressures near the main components of the 1903 Wright Flyer. (Photo Courtesy Cislunar Aerospace, Inc.) |

IE Alumna Uncovers Details of the

History of Flight

Dr. Jani Macari Pallis, BIE 1975 and MSHS 1977, is the author of the following letter, recently sent to friends at Georgia Tech. Dr. Pallis is the founder, chief executive officer, and president of Cislunar Aerospace, Inc., a San Francisco engineering, education, and research firm. Here, Dr. Pallis relates how she became involved with the Wright Again project and how it feels to help unfold history.

Some of you know that I have had the privilege of working with The Franklin Institute Science Museum in Philadelphia on a once-in-a-lifetime project regarding the Wright brothers. Our project is called Wright Again (www.wrightagain.com), since it follows the development of the first powered flying machine, the 1903 Wright Flyer. From the time the Wrights were young boys in 1878, making model helicopters, until December 17, 1903, the date of the first powered flight, Wright Again examines the Wright's steps and actions, provides a scientific explanation of what went right (or wrong) that day, and provides hands-on activity for students in grades 5-12. This collaboration began a few years ago when The Franklin Institute contacted Cislunar to use some of our educational materials on aerodynamics for kids created with NASA support (wings.avkids.com). We agreed and as a thank you, the museum director said to me, "You know if you are ever in Philadelphia, most of the Wright brothers' things are in the room next to me — come over and we'll put the white gloves on you and you can take a look."

Having done a bit of work on the Wright brothers for our first project, including the staff's aerodynamic simulation of the Wright Flyer (wings.avkids.com/Tours/wright.html), I thought I was pretty up on the Wright brothers, so I was puzzled. "What things?" I said.

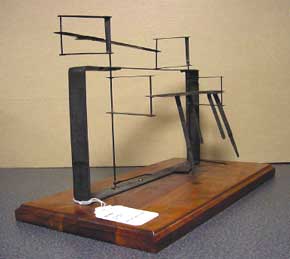

The orginal lift/draft balance on the flyer used by Orville and Wilbur Wright. (Courtesy The Franklin Institute Online, www.fi.edu. Copyright The Franklin Institute. All rights reserved.) |

This I had to see. I thought all those things were either lost over the years or at the Smithsonian. By the time I took a trip to the museum there was a new director, Karen Elinich, who just as gracious and is now the co-investigator of our project. There was drawer after drawer and box after box of drawings and artifacts from their workshop. As I looked, I would comment, "Oh, geez — you know what this is? This is a prop design....or this is a calculation for drag." The senior museum curator finally said, "We've had these here for 50 years, but we've never had an engineer look at them. We're all historians here." A few more conversations and our project, Wright Again, was born.

I am hoping you or perhaps colleagues, friends, pre-college students or educators you know might be interested in visiting our site or signing up for our monthly newsletter (see address below). All of our educational content is free, on the Web, and kid safe. There are a few different projects on the Wrights going on now, but I think Wright Again is more technically comprehensive and unique educationally than any of the others. Our project teaches basic forces of flight, structures, propulsion, and aerodynamics to kids.

Some of you have asked me to point out a few things that might be of interest:

For one thing, the first powered flight was not at Kitty Hawk. It was in a town four miles south named Kill Devil Hills. The Kitty Hawk area was selected for the high constant winds and because of all the sand — for soft landings!

So why are all those artifacts at The Franklin Institute and not at the Smithsonian? As the story goes, Samuel Langley (yes, as in NASA Langley and Langley, Virginia) was the secretary of the Smithsonian. The government funded Langley's research to create a flying machine. Just before the Wright's successful flight, Langley attempted the first flight — the plane ditched into the Potomac River a few seconds after it was launched. The Smithsonian later inferred Langley had built the first powered flying machine. Clearly this miffed the brothers. Although Wilbur died in 1912, Orville lived until 1948, and he was not interested in providing the Smithsonian any of the Wrights' work for many years. Subsequently, the 1903 Wright Flyer was housed at the Science Museum of London for years.

The Franklin had acknowledged the Wrights as first in flight almost immediately. Orville willed all of their workshop artifacts (now known as the Wright Aeronautical Collection) to the Franklin. His estate executors gave the brothers' letters to the Library of Congress and Wright State University. Orville had discussed bringing the Flyer back to the United States. In 1942, almost 40 years after the Wright's first flight, the Smithsonian wrote a suitable acknowledgement that satisfied Orville and after his death the Flyer was brought to the Smithsonian.

The right wing of the Wright Flyer is four inches longer than the left. The engine weighed about 50 pounds more than either Orville or Wilbur, and the operator would lay to the left of the engine. Bottom line, they needed more lift on the right wing, so it was made longer. Kids will learn that this is similar to a Venetian gondola. The gondolier stands to the left, adding more weight to that side, so the right side of a gondola is wider.

The first thing the curator of the museum gave me to look at was a wind tunnel journal. The journal has printed columns, perfect printing, bound in leather, every number clear and distinct, no scribbles, coffee stains, or telephone numbers in the margins. (You may recall that Orville Wright had a printing business before the bicycle shop.) I now know that this was Orville's handwriting. Wilbur's handwriting is not as neat, and he doodled and drew on things.

The construction of the wings of the Flyer was so flexible that I have better success explaining the wings of their gliders and the Flyer as a sail being rigged. The construction of their gliders and Flyer is so different from modern aircraft construction that sail construction is a better analogy. They actually flew their first gliders as a kite — no human on them.

The Wrights got involved in gliding and flying as a sport. Wilbur wrote more than once that there would never be any fame or fortune for the person that developed a flying machine. You may have heard them called bicycle mechanics — they were businessmen, technicians, engineers, and athletes. Orville was a competitive cyclist. Like many top athletes, Orville was involved in equipment design.

When the first safety bike (equal-sized wheels) came out at the turn of the century, Orville spent $160 for one. Wilbur waited until they were half price.

Although their father was a bishop in a Christian sect, Orville and Wilbur were agnostics, but they respected their father's Sabbath and did not fly on Sundays. The brothers agreed that they would not fly together, so that one of them could continue the work and for fear that the bishop would lose two sons in one accident.

Their mother was the handy one, she could build and fix anything — their mechanical talents came from her. (She died before any of their experiments started.) Both parents encouraged the boys to experiment.

An airfoil from the original Wright Flyer, part of the Franklin Institute's protected collection of objects. (Courtesy The Franklin Institute Online, www.fi.edu. Copyright The Franklin Institute. All rights reserved.) |

On the train ride home after an unsuccessful summer of testing at Kitty Hawk in 1901, Wilbur said to Orville, "Man is not going to fly for another 50 years." The brothers believed that the lift data they were using from other researchers was incorrect. They just didn't get the lift the charts claimed. When they got home, they built a wind tunnel, made small airfoils (wing shapes) out of metal, and in three months they had the most comprehensive set of lift and drag data ever created. Based on what they learned, variations of those wing shapes were made full scale and placed on the 1902 glider and the 1903 Flyer. Those airfoils still exist, and the Institute is allowing us to bring some of those airfoils to NASA Ames and test them to demonstrate the Wrights' work to young students.

There are some mysteries associated with those wing shapes. There is data for some airfoils that no longer exist. We are going to do some "reverse engineering" and see if we can determine what those shapes looked like. Kids can follow us and see if we can or why we can't solve the mystery of the missing airfoils.

One of the things we discovered was that a lot of the Franklin's Wright artifacts have never been on public display and many of the documents have never been published. So these materials are being digitized and will be available online. Students will use original Wright data in their calculations as they follow the project.

I've gone on long enough. There's an awful lot of work we have to get done and a lot to the project in general so I hope that you'll visit our homepage at www.wrightagain.com and pass the URL onto friends.

Interested persons may sign up to receive the Wright Again monthly newsletter at http://wings.avkids.com/Book/Wright/guestbook.htm

Dr. Jani Macari Pallis earned a master's in mechanical engineering from the University of California, Berkeley, and a doctorate in mechanical and aeronautical engineering from the University of California, Davis. Her firm, Cislunar Aerospace, Inc., has a strong interest in science education for children, and it has developed extensive Web content in honor of the December 2003 centennial anniversary of flight. For more information about Cislunar, see www.cislunar.com.

• Engineering Enterprise Home Page

Web Site © Copyright 2020 by Lionheart Publishing, Inc. and ISyE, Georgia Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher.

Lionheart Publishing, Inc.

34 Hillside Ave

Phone: +44 23 8110 3411 |

E-mail:

Web: www.lionheartpub.com

ISyE / Georgia Institute of Technology

Atlanta, GA 30332-0205

|

Web: www.isye.gatech.edu