WINTER 2003

COMPANY TRANSFORMATION:

![]()

A Case Study of

Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company

![]()

By William C. Kessler, Vice President, Advanced Enterprise Initiatives, Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company (LM Aero); Edenfield Executive-in-Residence, School of Industrial and Systems Engineering at Georgia Institute of Technology

Editor's Note: This article originally appeared in the journal Information • Knowledge • Systems Management, published by IOS Press, Amsterdam (Vol. 3, No. 1, 2002, pp. 5-14)

Lockheed Martin Aeronautics Company (LM Aero) was established in January 2000 from three separate Lockheed Martin Corporation aeronautics companies. The intent was to achieve one company, one team, and one vision that is built on the principles of customer focus and financial soundness.

This article describes:

A primary strategy of growth by merger and acquisition was replaced by a primary strategy of efficient and effective performance. The implications were significant.

In the winter of 1999, Dain Hancock was named president of LM Aero. LM Aero was the LM Corporation's consolidation of its three separate aeronautics companies: Tactical Systems in Fort Worth, Texas; Aeronautical Systems in Marietta, Georgia; and the Skunk Works in Palmdale, California. The consolidation established a company with a single profit and loss statement (instead of three). Mr. Hancock kicked-off the company transformation process in March 2000, at a two-day workshop in Fort Worth. Here are a few of the transformation relevant facts from that workshop:

Transforming an Enterprise Starts with Clearly Describing the Outcomes Intent 1: Restructure into one company, LM Aero, with a single vision and with exactly the right capabilities for the business of the new organization.

Intent 2: Deploy the LM Aero Concept of Operations that is driven by the principles of customer focus and financial strength.

Intent 3: Establish an organizational structure that aligns with the efficient and effective conduct of work, assures clear accountability, and has no unneeded redundancies.

"The Concept of Operations...How We Run LM Aero" (Ref 1) is proving to be a very important tool in communicating the intents of our transformation and providing a framework for the change process. For example:

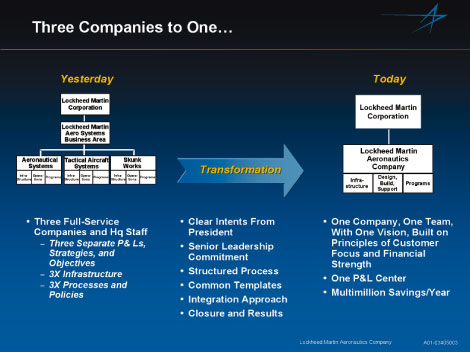

The Company Transformation Approach Figure 1 provides a summary of the input to and outcome of the LM Aero transformation. The outcome of the transformation is to be a company that operates to the clear outcome intents (Indents 1-3 above) and a company that initially operates with a specified reduction in overhead and infrastructure. Key enablers included:

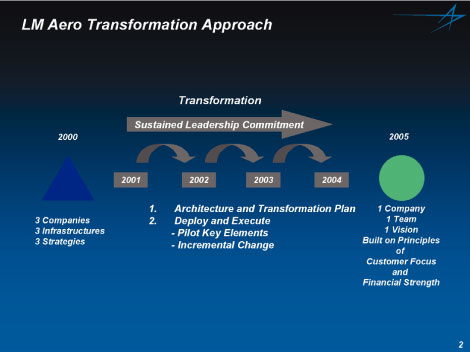

Figure 2 illustrates the flexible transformation approach being used. The overall transformation approach spans the 5-year imperative period as detailed in our Concept of Operations. The actual transformation has two significant elements:

For example, within our "architecture and transformation plan" element we have set the baseline process architecture and are designing our company-wide processes. The process architecture is a required enabler for LM Aero to become a process-centered company (Ref 7). Being process-centered will allow LM Aero to align operating capability with business requirements and to rapidly respond to intentional (and unexpected) changes. These two key characteristics — meeting our commitments and being responsive — are, in turn, central to achieving our LM Aero 5-year imperatives.

The corresponding "deployment and execution process" currently centers, for example, on "activating" the enterprise process owners (these enterprise processes all cross multiple organizational boundaries), designing the top-level enterprise processes, converging existing legacy processes from the three legacy companies, linking the enterprise and legacy processes, and managing by the resultant enterprise processes. Additionally, we have a "pilot project" underway related to supply chain integration. This "pilot" is defining the new roles and responsibilities of suppliers in LM Aero as well as "piloting" the approach for deploying all of our enterprise processes.

What about our near-term transformation intent: "complete the physical transformation to a single company in one year?"

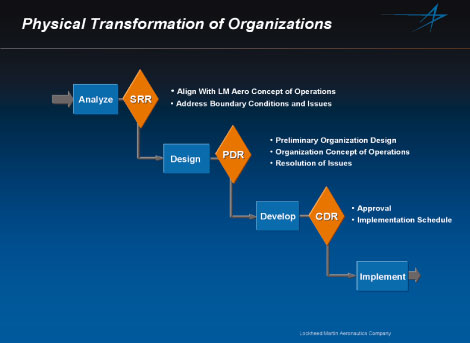

Figure 3 shows the organization transformation approach that was announced at the March 2000, kick-off workshop. The challenge was to move quickly to get the organizations in place to conduct the day-to-day business of the company. Speed was required, but the restructure needed to be done in a way that was consistent with the concept of operations and did not add significant barriers for the 5-year transformation process.

We used an approach and terminology that was familiar to our employees: system requirements review (SRR), preliminary design review (PDR), and critical design review (CDR). The basic intent at each of these review milestones was as follows:

This rapid organization physical transformation provided the foundation for the full LM Aero transformation process. The following items were found to be important to enabling this physical transformation:

Transformation Status, Results and Highlights Did we make any mistakes by pushing hard on organization designs before the process architecture was fully defined? Yes, but there are no detected organizational design flaws that are not being "cleaned up" as the organizational designs continue evolving in concert with the process architecture, 5-year imperatives, and specific yearly objectives. On the other hand, waiting until the process architecture was fully designed and vetted would have put the entire transformation initiative at risk. Most importantly, we must view transformation as being flexible and continually adjusting to new information...while keeping focused on the required outcomes (in our case, the concept of operations and our 5-year imperatives).

Were we finished at the one-year point? The physical transformation was complete. However, the "social transformation" was just getting started and the critical elements of the process architecture (consistent with the 5-year imperatives and concept of operations) were coming into a sharper focus.

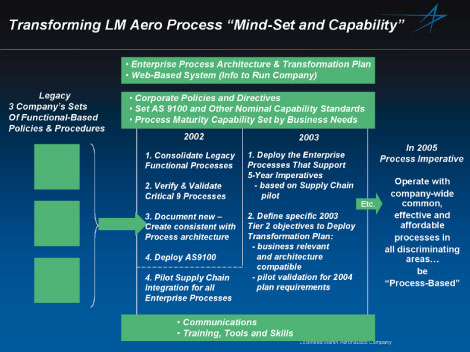

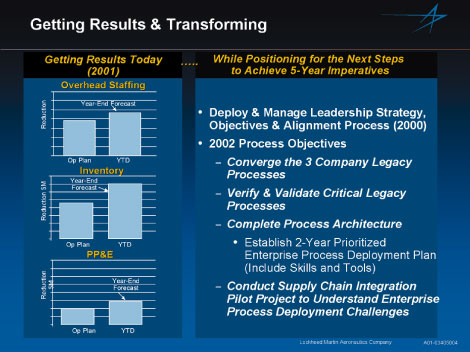

Figure 4 and 5 illustrate, with specific and real examples, some highlights from the transformation approach. Our architecture design work and transformation plan are continuous and will span the 5-year transformation process. However, the transformation plan is converted to specific and measurable one-year company objectives as illustrated by Figure 4.

Figure 5 further illustrates highlights from the transformation approach. The approach is very specific for the current year's transformation objectives while all the while designing the next steps (the next year's company transformation objectives) in concrete terms.

The highlights provided by Figure 5 reflect this incremental approach:

The objectives for 2001 (left panel) were achieved in 2001 and the next step plans (right panel) were converted into concrete, measurable objectives for 2002.

Complex, Large Scale Transformations Require Better Tools and Methods We started by defining the transformation outcomes for the new company. Next we focused on selecting and collecting the tools and methods needed for designing the needed organizational architecture and transformation plan. However, we came up empty when we looked in the "tool-box" for a version of systems engineering to use for "designing and building" an enterprise or an organization.

We found business "case studies," lists of "best practices," and many "special methods and tools" (balanced score cards, re-engineering, lean and Six Sigma, quality standards, maturity models, etc.)

We did not find any systematic methods for "designing and building" an enterprise to meet mission and design intents. One major barrier in establishing such a methodology is the inclusion of the qualitative aspects of all the people that comprise the enterprise. A second barrier is that business research seems to center on specific problems in an industrial sector, a company, or a part of a company. When applying these case studies and findings to a different company or enterprise, the result is often sub-optimized or not applicable.

Did we wait for new methods to be developed? No, of course not. We used our experience, our process architecture, and current literature (Ref 2-7) to guide the transformation approach and priorities. However, having a proven and systematic methodology would, most likely, have saved time and would have improved both our efficiency and effectiveness in the transformation.

Summary The body of transformation literature and our own personal experiences indicate that two specific enablers are required for successful large-scale transformations:

What has been accomplished in two years of the LM Aero transformation would have been impossible without having these enablers in place. One lesson we learned (again): conducting a transformation is hard work and must be tempered by realistic expectations and led by committed, experienced leaders. It is very easy to "draw up the transformation plan on paper" but it is extremely difficult to realize the plan's intent in actual practice. Why? Well, because human behaviors are involved in the process and the day-to-day business realities will challenge even the most "proactive" leadership as these realities compete for available time and other scarce resources.

Keeping the company engaged during a multi-year transformation process is very difficult. Our current experienced-based methodologies eventually get us through the lengthy process if the leadership is diligent and totally committed. But the time span required via our current process and methodologies can place the transformation initiative at risk.

Systematic methodologies for efficiently "designing, transforming and building" enterprises would be a most welcome addition to companies and enterprises where continuous organizational change and adaptation to external influences is now the "new normal" in business.

References Womack, J.P. and Jones D.T. (1996) Lean Thinking: Banishing Waste and Creating Wealth in Your Corporation, New York: Simon & Schuster.

Hammer, M. (1997) Beyond Reengineering: How Processes-Centered Organization is Changing Our Work and Our Lives, HarperCollins.

Murman, E., et al (2002) Lean Enterprise Value: Insights from MIT's Lean Aerospace Initiative, New York: Palgrave.

Rouse, W.B. (2001) Essential Challenges of Strategic Management, John Wiley & Sons.

Hammer, M. (2001) The Superefficient Company, Harvard Business Review, 77(6); 108-118.

Pall, G.A. (1999) The Process-Centered Enterprise; The Power of Commitments, New York: St. Lucie Press.

![]()

Background

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

The realities of the defense business in the post-cold war period converged for Lockheed Martin Corporation in 1998-99. In this time frame, the benefit of continuing defense industry mergers and acquisitions was questioned by the U.S. Justice Department and by the U.S. Department of Defense. Additionally, business analysts were touting tech stocks and questioning if any defense company would ever be able to perform efficiently and on a basis consistent with "expectations of the street." Lockheed Martin Corporation's stock price plummeted.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Our company transformation is centered on the following specific intents:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

There are many excellent references (e.g. see References 2-7) related to the topic of enterprise transformation, often called corporate reengineering. All of these have been reviewed and all have influenced, in some way, the LM Aero transformation approach.

![]()

![]()

Figure 1

![]()

![]()

Figure 2

![]()

Figure 3

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Efforts involving enterprise transformation can lose focus if the process is allowed to extend for too long a period without providing visible results. Ralph Heath, the LM Aero COO, led the company transformation process for the president. Mr. Heath established concrete and measurable milestones for the critical early phase of the transformation. The following represent typical objectives measures:

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Figure 4

![]()

Figure 5

![]()

![]()

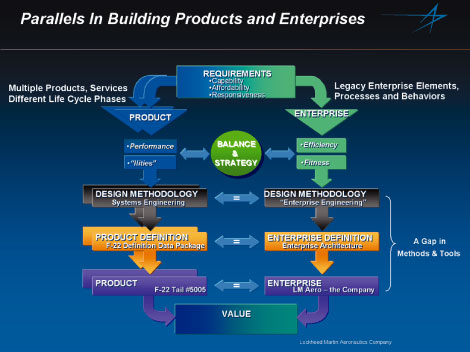

LM Aero has long been designing and building complex aircraft and, as a result, we have a premier systems engineering capability. Due to this history, it should not be a surprise that we took an approach to "designing and building" a new company that parallels what we knew about designing and building of new aircraft (Figure 6). This is what we know best and the terms (like SRR, PDR, and CDR) are already familiar within the company. In fact, our yearly deployment of transformation objectives is very similar to an aircraft "block upgrade" approach or what is now being called "spiral development."

![]()

Figure 6

![]()

The LM Aero physical transformation from three companies to one company was completed in one year. The transformation plan to achieve the company 5-year imperatives and to fully operate to the LM Aero concept of operations (Ref 1) is in place and is well underway.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Concept of Operations: How We Will Run LM Aero, Copyright 2020, Lockheed Martin Corporation

![]()

![]()

![]()

• Winter 2003 Engineering Enterprise Table of Contents

• Engineering Enterprise Home Page

![]()

![]()

![]()

Web Site © Copyright 2020 by Lionheart Publishing, Inc. and ISyE, Georgia Institute of Technology. All rights reserved. No portion of this publication may be reproduced in any form without the written permission of the publisher.

![]()

![]()

Lionheart Publishing, Inc.

34 Hillside Ave

Phone: +44 23 8110 3411 |

E-mail:

Web: www.lionheartpub.com

![]()

ISyE / Georgia Institute of Technology

Atlanta, GA 30332-0205

|

Web: www.isye.gatech.edu